why do girls go to the bathroom together?

on the cult of female friendships and the violence of perception, through the lens of Brutes by Dizz Tate. plus some media recs.

foreword: it’s fine if you haven’t read the book. I’ll start with a synopsis and a non-spoiler analysis, followed by breaking down the ending. Media recommendations are in between the two sections. Hope you’ll enjoy!

Two summers ago, girlhood earned its place in the internet discourse hall-of-fame—among words such as gaslighting and genres such as sad-girl-melancholia. Everyone has watched Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999), and we can all recite the fig tree passage from The Bell Jar backward. Our collective fascination with girlhood, I’m sure, will be a discussion for 2050 anthropologists and psychoanalysts.

Despite a 3.15 rating on Goodreads, Brutes by Dizz Tate should be among its predecessors in what I call the “mandatory girlhood reading list.”

i. synopsis

one-sentence synopsis:

Girls reminisce on their collective obsession with the preacher’s daughter, who has gone missing.

vibe check

Sitting on your porch during an extreme heatwave, surrounded by thick smog and staring directly into the setting sun.

similar books

The Girls by Emma Cline

Inspired by the Manson family, a story of Evie’s obsession with an older girl.

—Similarities: hazy vibe, ominous, fascination with older girls.

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffery Eugenides

From the memories of teen boys, an account of the Lisbon girls.

—Similarities: hazy vibe, male gaze, romanticization.

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley

A group of girls who are pregnant and find support with one another.

—Similarities: girls finding safety in numbers, small town.

ii. essay (non-spoiler)

Through the hazy lens of memory, Brutes reminisces on the unspoken intricacies of female friendships. The past timeline feels meandering, obsessive, and romanticized; the present-day narrative processes the bleak aftermath of that summer. Dread weighs on your shoulders, hanging on even after the last page. The interwoven timelines portray nostalgia for girlhood, alongside themes of memory and scopophilia. I can’t stop comparing Brutes to books about cults. Is that the nature of female friendships?

In Brutes, the girls worship the male gaze and see older girls as God. They move as a group, embodied by its first-person collective (“we”) point-of-view. They commiserate about wanting male attention—a covert competition and their only commonality. Yet, only with each other, do they cease being objects of the male gaze. Perhaps that is why they find safety in numbers—protected from the violence of perception. Yet, receiving romantic attention is a cause for ostracization. Doesn’t this sound cult-like?

“We cannot believe [character] has become pretty without us noticing […] We assumed she belonged to us so wholly that we had forgotten to.”

Part of female friendship is the joy of being among girls. When my friend entered into a serious relationship, she received scrutiny regarding her boyfriend. “It’s like you’re cheating on your friends with your boyfriend!” That was my conclusion. Female friendships often feel so intimate that the threat of a partner (or even a new friend) becomes a betrayal. (Notice the language: “belong!”) Romantic attention is a hostile reminder of the reality, one where male approval is survival. More than jealousy, the girls resent their friend for bursting the bubble of a world where the male gaze doesn’t matter—hence the sudden realization that their friend is “pretty.” The girls learn that to be watched is to be loved; to be ignored is to be free. This is the paradox that anchors Brutes.

“To imagine you are loved is to imagine you are watched all the time.”

“No one looks at us and this gives us a brutal power.”

The girls hyperfixate and spy on Sammy and Mia, older girls who appear loved and free, an ideal defiance of the paradox. Their spying is ironic, as their binoculars make Sammy and Mia into objects of their gaze, projected upon instead of humanized.

The setting is hauntingly atmospheric: it’s a character in itself. Wealth disparity is a wall that separates the town in two, yet both factions unite over religion and fear of the lake—which a nearby fertilizer factory pollutes. The girls, starry-eyed for Hollywood, yearn for a casting agent’s approval.

Yes, Brutes is confusing. You seem to follow girls who wander around the town, but the story is in the subtext, through symbolism and such. My spoiler-free explanation is that the symbols mimic the fragmentation of memory. Let’s leave it at that, since ignorance is bliss. If you’ve finished the book (or don’t care about spoilers), stay for the next section, where I break down the book and argue that symbolism is necessary, answering the titular question: why do girls go to the bathroom together?

Feel free to skip to part 2 (analysis), which is the section right under this one.

interlude: weekly media

books

I finished Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar. It was delightful and one of my new favorites! It has a Fleabag feel: cynically funny, but also existential.

substack

offline diaries: three weeks without social media

not using your phone makes you realize a lot of things about yourself

so you want to listen to classical music? (part I)

putting my MM (Master of Music) to use: an ex-concert pianist and her friends share 100+ must-know solo piano works.

youtube

iii. essay (spoilers!!)

Since this is the top Goodreads review, I’ll break down my interpretation. When I realized the symbols’ meanings, it all clicked—and got really dark.

TW: CSA

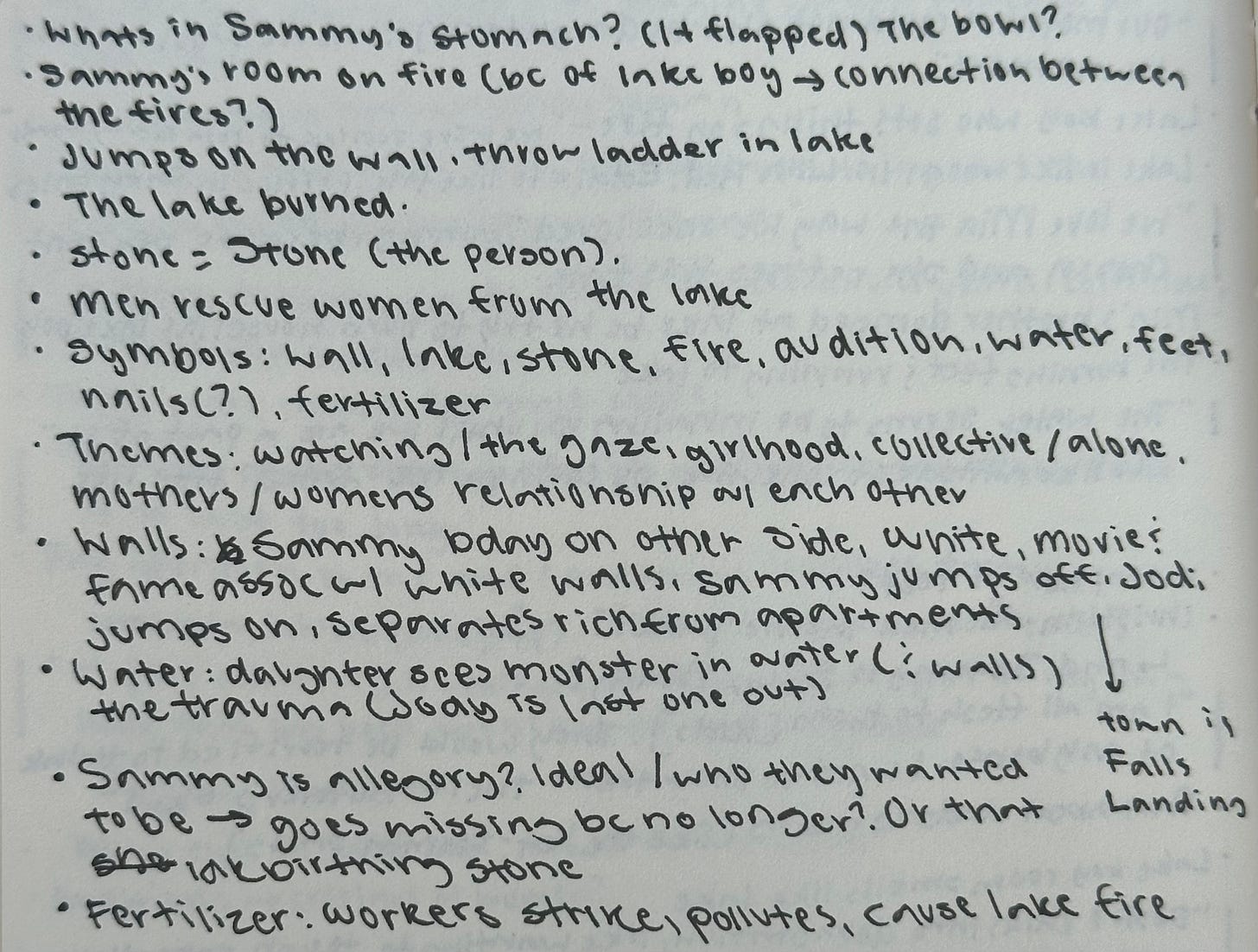

what’s up with the end?

The girls are taken to Stone (the casting agent), who coerces the girls to give him a massage (a euphemism, obviously). In the last paragraph of chapter 14, every sentence begins with “we” as the narrative becomes increasingly surreal: clocks turn backward and the girls move in reverse. This out-of-body experience portrays the girls’ dissociation during their SA. Then, the narrative suddenly switches from “we” to “I.”

“I look around for someone else to be but I am alone and I have always been so scared of being alone.”

This is why the girls move as a collective. There’s safety in numbers because you can pretend you aren’t the object of a man’s gaze; when you are alone, you can no longer delude yourself. When the narrator is left behind, for the first time, she confronts the violence of the male gaze. In my interpretation, the assault is a literal representation of the male gaze’s cruelty.

“He looks at me in such a way that I feel I am being created for him. I do not want to be his mirage. I do not want him to make me.”

That is the violence of the male gaze—one that recreates you into an object for his consumption. His idea of you is not you, but you’re helpless against it. The greatest horror is losing ownership over your essence, existing only as a man’s conception.

If you still aren’t sure about what just happened, the next chapter depicts a syringe (of feces) ejecting into a balanced bowl of pure water. It’s like Dizz Tate didn’t want us to miss what just happened! Unable to confront the truth, the girl uses symbols to articulate her experience. Chapter 15 then encourages us to read into the novel’s other symbols—perhaps they, too, are representations of what had happened?

Let’s finish breaking down the ending first.

In my interpretation, Jody was left alone with Stone. Her chapter follows the SA chronologically, with all of the other girls asking if she’s okay after she leaves Stone’s room. After that, however, we’ll need symbols to help us understand.

symbolism…

Tate tells us to pay attention to symbols.

“We realize the woods are not woods, and the wolves are not wolves. In these stories […] the mothers are always banished or dead.”

Little Red Riding Hood is a pretty apt comparison for understanding Brutes: the lake is the forest, and the Big Bad Wolf is Stone. Here, the lake is not just a lake, and stones aren’t just stones.

stones

Sammy births a stone, and a stone bruises Britney’s leg. Remember how the casting agent’s name is Stone? And how, during Jody’s SA, she compared his thoughts to pebbles? Jody describes the “silence deep inside [herself]” as:

“A cavernous silence, where his thoughts are pebbles, skipping stones thrown far away.”

The stone could represent the girls’ trauma—after all, they’re Stone’s thoughts, which are connected with his objectifying gaze. Thrown far away, the pebbles are buried deep inside Jody as she suppresses her trauma. This would explain Jody’s anger at the stone because earlier, she was angry at Stone. If the stone represents trauma, then Sammy has also been assaulted by Stone. Why does Sammy birth it? Maybe she’s trying to forget about it, which requires the pain of confronting it? I’m not quite sure (unlike what you may think, I’m not all-knowing).

the lake

I’m less sure about the lake than I am about the stones. Let’s look at what we know about the lake: don’t go near it. That, and Mia pushing Leila into the lake—which sounds awfully similar to taking the girls to Stone. When the girls fall into the river, they surrender to its stillness and darkness, similar to Jody’s experience during her SA. Jody is the last one pulled out of the lake, and she is the last one left with Stone. The darkness of the lake also corresponds to Jody’s metaphor in chapter 15. The syringe injects feces into clean water; the fertilizer factory contaminates the lake. (Fertilizer is made up of feces, I’m pretty sure).

The lake is just a really large bowl of water.

The lake could represent the girls’ collective trauma—hence Sammy’s stone falling into it. That’s why the mothers tell the girls to stay away, as if a cryptic warning is enough to protect their children from predators. If the fertilizer factory’s unrelenting pollution can be compared to the girls’ trauma, then Tate portrays a world in which violence against girls is systematic and constant—and most of all, ignored. That is why Jody is so frustrated at the end, when everyone leaves and dismisses the monster in the lake. Workers protest against the fertilizer factory, but pollution persists. I’ll let you work out these parallels yourself, since you’re now amazing at understanding symbolism! The lake erupts because eventually, the suppressed trauma will boil over.

Understanding the girls’ trauma explains the symbolic narrative of Brutes. Like the metaphor in chapter 15, Tate uses symbols to mimic the girls’ memories, which are so tainted by trauma that they become surreal and disjointed. Unable to confront their assault, the girls turn their trauma into symbols. The story is told in the collective because it is comforting, and too many girls are familiar with the experience of violation (at least via the gaze).

Brutes, it seems, is one big fairytale. On a meta level, it’s as confusing and nonsensical as the cautionary tales that were supposed to protect girls against predators. Do you get my love for it now?

Afterword: if you enjoyed this essay, you may also enjoy this one, which goes way deeper into the male gaze:

ughhhhh so true. adding brutes to my list rn!!

I loved this and ordered Brutes immediately after reading, I can’t wait to read it 💗