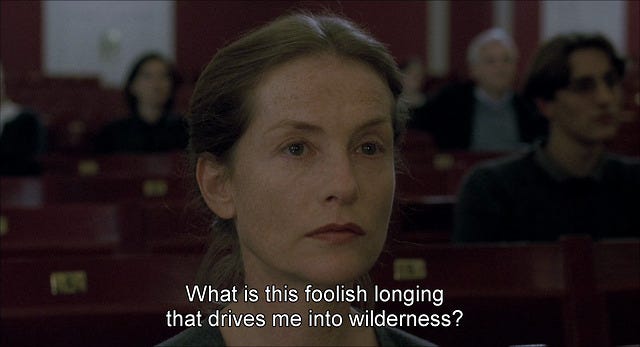

deconstructing the male fantasy: an analysis of The Piano Teacher

on the male gaze, female suffering, and illusions of power: a deep dive into gender relations in The Piano Teacher.

Haneke’s The Piano Teacher (2001) is a beloved cult classic. While I have yet to see the film, its source material provides one of the most compelling character studies I’ve ever read. Elfriede Jelinek even won the Nobel Prize for her novel—if that matters to you. Which is to say that in this essay, I am exclusively discussing the novel. If you’ve only watched the movie, feel free to stick around anyway since there are no major differences!

In this essay, I will deconstruct Jelinek’s portrayl of the male fantasy and analyze its influence on Erika and Walter—focusing on Erika’s letter and its aftermath. Ultimately, I will try to argue that the conflict during the climatic scene arises from Erika’s attempt to escape institutional violence against women while Klemmer faces pressure to reinforce the patriarchal order—with both urges perpetuated by the male fantasy of objectifying and “conquering” women.

(Notes: This essay does not necessarily reflect my view on gender relations, as I tried to set my opinions aside to stay close to the text. Also, there are no page number citations because I read it online. You have to trust that, unlike ChatGPT, I do not make up quotations). Now, let’s get started.

male gaze as an objectifying force.

The gaze is so central to The Piano Teacher that it is impossible to miss.

Erika goes to peep shows and watches couples have sex; schoolchildren gawk at pornographic advertisements. Jelinek’s Vienna is a scopophilic (voyeuristic) heaven—a park is even nicknamed “the homeland of the peepers.”

What even is scopophilia?

“[Scopohilia] continues to exist as the erotic basis for pleasure in looking at another person as object.”

Laura Mulvey. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (October 1, 1975), https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

In line with Western gender roles, men typically assume the role of the “surveyor,” transforming women into objects that are “surveyed.” Needless to say, there’s a power disparity between the subject (men), and the object (women). This sounds an awful lot like the male gaze, a word that took TikTok by storm in 2023—because Mulvey also coined the term “male gaze,” referring to heterosexual men’s tendency to objectify or sexualize women. While her definition usually refers to the portrayal of women in the visual arts and literature, it doesn’t take long to internalize the lenses created by media. Thus, for women in Jelinek’s Vienna, “the only things that count are creases, wrinkles, […] and loss of the figure.” Their worth is tied to their function as sexual objects. The prevalence of scopophilic opportunities frames the culture as one that is concerned with the objectification of women. That, however, does not seem to be enough.

Let’s look at the pornographic film that Erika visits:

“The object makes an imprint in her flesh, showing the viewer who’s boss and who’s not, and the viewer too feels he’s boss.”

Elfriede Jelinek, The Piano Teacher.

The self-insertability of the film (think Y/N in fanfics) is a byproduct of the male gaze: created from the male perspective and for the pleasure of men. Duh! From TV programs—which, unbound by societal norms, feature a heightened reality—we glean the clearest access to the male fantasy. The appeal of pornography is allowing the viewer to take pleasure in sensationalized and unrealistic scenarios. More importantly, the TV (referred to as a “miniature world”) is a symbol of fantasy throughout the novel. While Jelinek often refers to the TV, this is one (of two) instances when we “watch” TV with the characters; the other is when a man threatens a woman. In both scenarios, the fantasy involves a woman’s suffering: the first is physical, the second emotional. Considering that the pornographic film is a public showing, as opposed to a private one, this scene reflects female suffering as a fantasy of the masses.

(Note: before I get canceled, the male fantasy probably does not apply to all men. In this essay, I’m only analyzing within the scope of the novel).

More importantly, does the male fantasy require women’s suffering?

Suffering.

While not a direct answer to the question, in Seminar X: Anxiety, psychoanalyst Jaques Lacan argues that feminine masochism (a Freudian theory that asserts masochism as a feminine characteristic) is a male fantasy, rather than a female trait.

Jelinek doesn’t contradict this spectacle of female suffering.

“Becuase of her suffering, this woman deserves every ounce of male interest she can squeeze out. The young man’s interest is then harshly reawakened.”

Elfriede Jelinek, The Piano Teacher.

Jelinek presents a causal relationship between female suffering and male interest, one that the characters are aware of. Rather than a separate category of the male fantasy, female suffering is the highest degree of objectification. Okay, I guess it’s time to talk about the letter.

The Letter.

In the letter, Erika presents herself as the male fantasy, which we’ve hypothesized to consist of objectification, whose best-case-scenario involves suffering.

objectification.

Erika repeats her desire for Klemmer to turn her into a “package that is completely at [his] mercy.” Her wording mirrors Klemmer’s earlier desire to “unwrap this package of skins and bones.” Her other demand of bondage also limits her autonomy, such that her physical capabilities reflect that of an object.

I also think that the diction is pretty significant. The verb tense of “package” suggests a manufactured appearance, which mirrors Erika’s becoming of the male fantasy.

suffering.

Pretty obvious. But if you’ve forgotten the letter’s contents, her letter revolves around suffering. A lot of it, actually.

But Klemmer, as we all know, didn’t take her letter well. Why is that?

brief analysis of Erika.

(an interesting rant that’s somewhat related to the thesis. feel free to skip)

We have yet to discuss the significance of Erika-the-voyeur (a traditionally “masculine” role). There are, as always, multiple theories. But the most obvious (and the most relevant) explanation is her desire for power as a form of self-protection. Erika sums up the unique power granted to the female spectator:

“She doesn’t want to take part, but nothing should take place without her.”

Elfriede Jelinek, The Piano Teacher.

Rather than the pleasure of self-insertion into sexual fantasies (which, in its male gaze-y perspective, is inaccessible to Erika), Erika goes one step further. She, as the spectator, is in control of both people in the encounter through a god-like omnipotence. In the example of the pornographic film, she feels control over the suffering woman (a power that male spectators experience) and the man who inflicts cruelty on her. Her power over the woman occurs because she controls the man; if she wants him to stop, she can. Yet, that is precisely why she seeks out violent encounters. As the degree of cruelty increases (along with the man’s power), the more powerful she feels in her ability to control him. Considering Erika’s abusive mother (an essay in itself), Erika’s desire to control the abuser would make sense. Does this sound familiar? If not, it will.

what even is the male fantasy.

Let’s discuss—through the most ironic passage in this book—Klemmer’s fantasy of Erika.

“She ought to […] turn herself into an object that she can then offer to him.”

Elfriede Jelinek, The Piano Teacher.

Then, not even 100 words later:

She should be a free person, presenting herself to Klemmer, who is fully informed about her secret desires”

Elfriede Jelinek, The Piano Teacher.

Poor Klemmer is conflicted between viewing Erika as a free person and as an object. This conflict resolved itself when I remembered that he idolizes Cassanova. She can only “choose” him if she has free will; without it, the triumph of “conquering” her is no more than that of buying a house. His idea of Erika as a free person is entirely self-serving—rather than humanizing. He decides that she has will, rather than acknowledging her intrinsic agency as a human. In short, Erika remains an object to be conquered by Klemmer, except she now has the property of free will.

But still, Erika follows his blueprint: she uses her will to objectify and present herself to him (through her letter). So what went wrong?

Remember that Klemmer, first and foremost, wants to “unwrap” Erika and to “possess what’s underneath.” The vagueness of what’s-to-be-uncovered is the backbone of the male fantasy. Simone de Beauvoir’s idea of women’s label as the “Other”—while men assume the role of the self—is especially pertinent. While men are individuals, women belong to the collective of the other. Through this categorization, men dehumanize women by denying their individuality and complexity. Klemmer’s fascination with Erika as a mysterious other, while not attempting to actually know her, fits into Beauvoir’s narrative. For Klemmer, unveiling Erika’s “secret desires”—which, for him, represents the inner world of the other (AKA all women)—allows him the “experience” he desires from his relationship with Erika.

Where Erika misstepped in her letter is denying him the opportunity to unveil her. It goes without saying that this [metaphorical] act of undressing is related to an assertion of power; similar to colonialism (consider the feminization of land, which waits to be conquered by men), uncovering Erika’s secrets is an act of power. What greater triumphs are there than discovering the mystery of an entire sex? Alas, we understand Klemmer’s fantasy: Erika should choose to offer herself as an object for him to unwrap.

brief analysis of Klemmer.

(like before, feel free to skip because it’s not that relevant to the thesis)

For Klemmer, Erika is a representation of Lacan’s objet petit a—the object (which doesn’t exist) that would completely satisfy all desires. Because the objet petit a doesn’t exist, Klemmer mistake something (Erika) for the objet petit a, which elevates the thing to its separate pursuit, only to become frustrated when it doesn’t satisfy his desire. The lack, which drives the objet petit a, is something to be enjoyed repetitively, similar to collecting Pokemon cards. Applied to Klemmer’s desire to “unwrap” Erika and understand the other, this is his second reason for personifying her: an object is surface-level (and can only be explored once), while a person’s psychological depth allows for continuous projection of what “could be.” After each stage of uncovering, Klemmer can always convince himself that there is more to be found—therefore sustaining the lack and allowing him the maximum enjoyment in the process of overcoming. Erika’s psychological depth, like her will, is given as a means for his pleasure.

Klemmer’s reaction.

We now understand why Klemmer is upset.

“However hard he now tries, he can no longer see her as a human being; you’ve got to wear gloves to touch something like that.”

Elfriede Jelinek, The Piano Teacher.

Erika has unwrapped herself; in doing so, she violated Klemmer’s second reason for viewing her as human (which I explained in “brief analysis of Klemmer”). Therefore, in his eyes, she is reduced to an object that he can only explore once. Paradoxically, the letter is her attempt to become Klemmer’s equal: to exert her will and reflect her psychological depth. The letter is akin to a contract—or at least sheet music. In the same way that Erika conducts private lessons, she shuts Klemmer into her room and asks him to read the letter. Much like how she is in control as the teacher, she exerts agency in initiating the masochistic arrangement. (Notice how Klemmer repeatedly asks about his gains from the arrangement?) In classical music, the sheet music is binding: to stray off-script is unheard of.

“As established, masochism is enacted and the rules set out contractually by the ‘victim’. For woman, this means she is able to escape the institutional and sadistic violence, which permeates society.”

S. Žižek. The Metastases of Enjoyment: On Women and Causality (Verso, 1994), 92.

Erika’s masochistic contract does not comply with the male fantasy because it is only an illusion of power. If you read the section “analysis of Erika,” this contract is, once again, a form of self-protection. As with her voyeuristic adventures, Erika gains power because now, “nothing should take place without her [contract].” As the contract’s writer and initiator, Erika feels as though she is in control of Klemmer—which explains the letter’s focus on threats of violence. Stopping at threats requires Klemmer to overcome the male fantasy [of female suffering] in favor of Erika’s contract, which is the utmost submission to her power. Unfortunately for Erika, Klemmer recognizes this.

The climactic scene (not the ending), as you’ve probably guessed, is his attempt to restore societal order.

Conclusion.

Jelinek’s elaborate set-up of Viennese society prepared us for the climactic scene. Like Erika, we (as readers) know how the society functions. Despite Erika’s attempts to familiarize and package herself into the male fantasy, she fails to protect herself against violence. Young Klemmer’s coming-of-age in this novel revolves around his discovery and restoration of the patriarchal societal order, which has reinforced itself since his childhood. How bleak!

Bibliography

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. London: Vintage Classics, 2015.

Jelinek, Elfriede. The Piano Teacher. Translated by Joachim Neugroschel. Grove Press, 2004.

Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. New York: Norton, 1998s.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16, no. 3 (October 1, 1975). https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

Žižek, S. The Metastases of Enjoyment: On Women and Causality. New York: Verso, 1994.

i’m saving this one for later because the book is on my tbr!!

mañana iré a la biblioteca a pedir el libro, hace mucho quiero leerlo y este artículo me lo recordó<3